Recipes: Our Culture of Food

The Story of Food

It was only yesterday – a geological instant in earth time – that our forerunners cast that first stone and realized that they had discovered a tool that might transform their lives. Our species went on to invent countless other tools, and indeed, we often think that it is our development of tools – even weapons – that defines man on this planet. With our modern tools, we no longer can get lost. When our heart grows tired, we can dial in a new one. If we don't like the face we were given, we can change that. We can talk to Patagonia or Easter Island from our pocket. There appears to be no limit to the awesome power of our inventions: with only one finger on a button, we can even wipe out the human race, although we have yet discovered no way to ensure that evolution would do a better job the next time around, or that there would even be a "next time."

A casual visit to your local emporium of kitchen wares reveals an unlimited array of tools we have developed for cooking. It is not even apparent how many can be used. You discover not just a variety of useful spoons, forks, and knives; there is a mixer, grinder, beater, chopper, cleaner, cooler, or cooker for almost everything edible. And we also have machines to work off all the calories we eat and keep our vanishing muscles from disappearing entirely. Is this plethora of tools the best measure of how far we have come since we threw that first stone?

In our technological age, we often presume that it is our development of tools that has primarily marked our evolution as a unique species, even though many other animals and birds also use tools. But Lewis Mumford and other thinkers have exposed how mistaken it is to define man as a mere tool-using animal and have understood that it is the development of human culture that sets us apart from other life on this planet: our language and our capacity to learn and anticipate, to process abstractions, to record and preserve our experience and transmit to others what we learn.

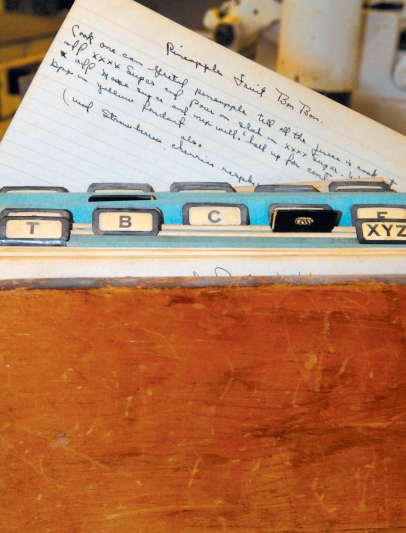

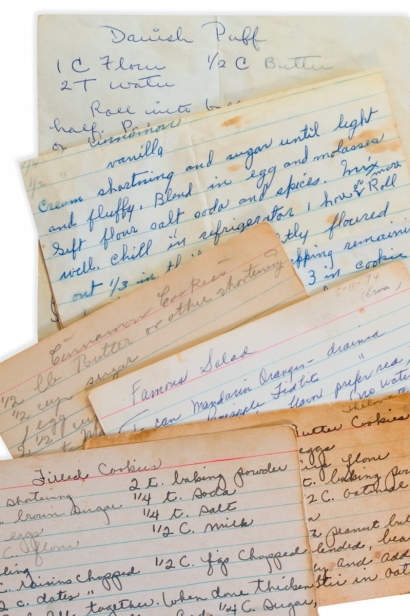

And what, you may ask, does this insight have to do with the story of food? Do not all our fancy kitchen implements make a great chef and fine meals? Not at all. It is shared knowledge and experience and love of food that, with nature's bounty, make a great meal. In our story, it is the human culture of food, and not machines, that have been determinant. We record and transmit our "culture of food" in the form of recipes. Cookbooks fill our shelves, and much of this culture is passed by word of mouth. The beginning French cookbook is called "1,000 Recettes," no less. And an internet search for how to cook an egg yields 72,100,000 possibilities in .38 seconds! Our cultivation of food is hardly new and must have begun with the first Paleolithic gatherings of humans with nature's offerings. It has developed as a skill and an art over tens of thousands of years. Dozens of types of sausage have been found in the ruins of Roman villas, not to mention elaborate Chinese recipes that are thousands of years old.

It is the development of our language and ideas about what we eat, transmitted from the past and shared, that tells us where we have been, who we are, and how we hope to live, and that sets us apart from our animal cousins. The story of food is the story of an amazingly endless variety of ideas, obstinately embellished over time by human ingenuity, about how to grow, prepare, and consume nutritious and flavorful food. Notwithstanding all this history, we are still learning and inventing. It may take no more than a pot to boil an egg, but it takes the history of human know-how from your grandmother (or someone else's grandmother) to make most anything else. We do that every day without being aware of our debt, not to machines, but to human culture that began many thousands of years ago.

"There is good reason to believe, indeed, that man used an immense variety of foods, far beyond the range of any other species, before he had invented any adequate tools. The constant practice of searching, tasting, selecting, identifying, and above all noting the results. . . was, I repeat, a more important contribution to man's mental development than ages of flint-knapping and big-game hunting could have been."

–Lewis Mumford, The Myth of the Machine (Harcourt Brace & World, Inc., New York, 1966)