The Sweet History of Connecticut Pork

Pork was a treat that early American families would look forward to all year. On a cool, fall day of a good year in colonial Connecticut, when the rye was reaped and the pumpkins picked, a pig roast would have been the culmination of the harvest. It was both a celebration of the growing season and a preparation for the long winter. Proper butchering was a complicated process for a family, and it usually took several days, performed with attention and care. Organs chopped and boiled with allspice and butter yielded a tasty gravy when added to the dripping pan. Then, as Lydia Child wrote in The American Frugal Housewife, “when the eyes drop out, the pig is done.”

In early Connecticut, pork was a staple food and an important source of protein and good health. As early as the 1600s, as the colony brought in livestock from Europe, the number of corn-fed pigs increased more quickly than dairy cows, and a market for pork sprang up and grew as the century progressed. In fact, by the 1750s, Connecticut’s “fat hogs” (weighing 500 or 600 pounds) were exported and considered “far superior” to all others in America by the English. Merchants from Boston or New York who mixed “inferior pork with that of Connecticut” were scorned. Packed in tight layers, salted and brined, and with a heavy stone placed on top to ensure the meat stayed down, our state’s pork became a delicacy in England.

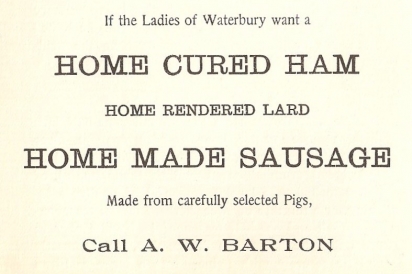

Of course, not all pork was meant for export. Local farmers and cooks alike used the entire animal, rendering fat, salt-curing the meat, and making dishes like souse: ears and feet boiled until tender, split, and laid in a deep dish. To that was added hot vinegar steeped with cloves, peppercorns, nutmeg, and salt. When cold, the mixture was often sliced, pickled, or fried in lard. Cooks also came up with interesting ways of eating the preserved meat. One popular method was to soak thinly sliced salt pork in hot water, dip it in beaten egg wash, roll it in bread crumbs, and fry it in hot fat. This could be served with mashed potatoes under a creamy ladleful of gravy.

Another popular dish in rural Connecticut was sliced pork with apples. Cooks would fry the pork, drain off the fat, slice apples and sauté them until “tender and brown,” and combine the two on the plate, sometimes adding sliced cold potatoes for a more filling dish. Indeed, this mix of sweet and savory has always been part of traditional New England cuisine. 19th century additions like brined and fermented cabbage added a third “sour” element. However, even 17th and 18th century Connecticut cooks used sour vinegars in many recipes, intriguing taste buds while providing a practical way to make food last.

Though we might think of colonial cooking as simple and bland, settlers explored the same flavor principles that had been practiced for centuries. Sweet and sour pork is a combination associated with Asian cuisine today, but the ancient Romans roasted wild boars with honey and vinegar, and this practice survived into the 1600s in Europe. Swine had been the preferred meat source for England during medieval times, and the old recipes traveled with British colonists as they populated America.