The Slow History of Hasty Pudding

The first Connecticut colonists found corn-based dishes practically inedible. The niece of Governor John Winthrop wrote to him from Stamford in 1649, happily declaring that her generous husband ate corn, so that she could eat wheat. Not only did their European stomachs find the gritty grain hard to digest, their initial prejudices singled out corn as a Native American food, which they considered sinful and “tainted with savagery.” However, since wheat grew poorly in our rocky soil, they had few other choices, so they learned how to plant and cook this “turkey wheat.”

Corn in colonial New England was tough to chew, so Native Americans combined it with beans and squash or ground it into cornmeal, soaked it in water, and fried it. The colonists adapted their methods, using animals’ intestines or cloth bags to slowly simmer the cornmeal into what they called a “pudding.” This “hasty” or “Indian” pudding became a staple of early Connecticut diets, but even mixed with other foods like fruit, meat, or nuts, it was a decidedly unpopular dish, receiving little but scorn for the next 100 years.

However, as European stomachs adjusted, hasty pudding became a healthy and tasty part of the meal and was often served as a side dish, like a traditional English pudding, or fried for breakfast. There were three versions alone in our country’s first cookbook, American Cookery by Amelia Simmons, published in Hartford in 1796. Simmons and others suggested scalded milk instead of water, eggs, molasses, and spice. All agreed that “the preparation of this pudding cannot be hurried.” The cornmeal needs to absorb liquid and thicken slowly, or it “will be spoiled.”

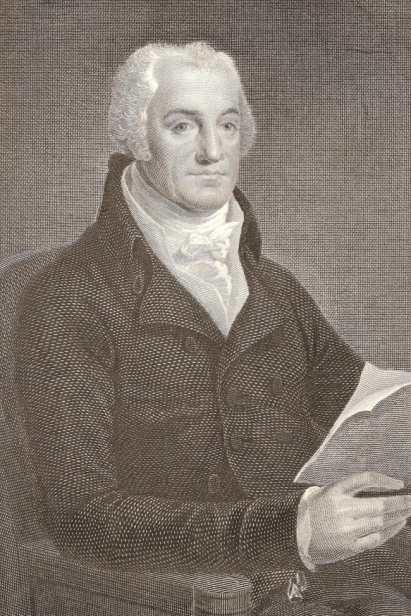

By the 1800s, the people of Connecticut felt a keen nostalgia for this meal. While touring Europe, author and diplomat Joel Barlow wrote the famous, mock-heroic poem, The Hasty-Pudding, after a meal of the Italian variation of this dish, polenta.

I sing the sweets I know, the charms I feel,

My morning incense, and my evening meal,

The sweets of Hasty Pudding. Come, dear bowl,

Glide o'er my palate, and inspire my soul.

A half century later, Harriet Beecher Stowe spoke of the Indian puddings of her youth with the same longing. But by then, the dish was already shifting from a breakfast food to a dessert. This was due to the growing availability of wheat from huge Midwestern farms and sugar cane from the Caribbean. As American taste buds became accustomed to sweeter dishes, more sugary recipes were created. A recipe from Torrington in 1904 even suggested putting layers of “boiled frosting” between tiers of Indian pudding to make a “layer cake.”

Into the 20th century, Indian pudding remained a common dish, featured in such places as Connecticut Magazine. As corn itself became sweeter, though, cooks turned to fritters, chowder, flap jacks, and roasted ears as the best ways to prepare this vegetable. As cornmeal faded from the northeast in the mid-20th century, Indian pudding, unfortunately, disappeared from restaurant menus, remaining primarily in inns and taverns as a nostalgic throwback.