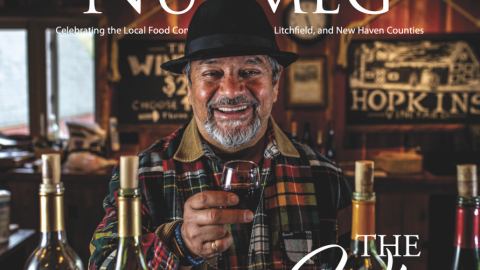

Growing Grapes in Connecticut

Philip Jamison “Jamie” Jones is a sixth-generation farmer at Jones Family Farms in Shelton. In 1999, he planted the first grape vines at Jones Winery and has been tending them ever since. We sat down with Jamie to discuss what it takes to grow wine-producing grapes in Connecticut and what an increasingly erratic climate may mean for the future of doing so.

What makes it possible for wine grapes to do well in Connecticut?

Although, geographically, we’re a relatively small state, our grape-growing climate does vary depending on where you are. Most grapes do well in warmer, almost maritime climates, where a large body of water modifies the extremes of both hot and cold weather. So I’d say, wineries in the southern half of the state do benefit from the modification of Long Island Sound. The northern half does get some benefit but not quite as much, so they have to be a bit more careful about what they plant.

The other thing to look at is the soils, which also vary widely depending on what part of the state you’re in. Where our farm is in southwestern Connecticut, we’ve got a fine, sandy loam. It’s generally kind of rocky, with a variable topography. We selected the sites on the farm with south-to-southwest facing slopes [to maximize sun exposure], with well-draining soils [to maximize root growth] for the siting of our vineyards.

What grapes are you growing at Jones Farm?

In southwestern Connecticut, we’re able to grow some [Vitis] vinifera [the species of grape most commonly used for wine making, of which there are thousands of varieties] but don’t grow vinifera exclusively. We also grow some of the French-American hybrids. The vinifera that grow best on our farm, and really the only ones that can grow reliably in Connecticut, are ones found in northern Europe, like Alsatian whites, specifically Riesling, Pinot Gris, Gewurztraminer. We have a little Muscat Ottonel, and of course, the old white standby that grows just about everywhere and that everyone’s heard of, Chardonnay. We’re finding that these white varietals grow well here and are capable of producing world-class wines.

There is only one red that truly stands out, and that’s Cabernet Franc. My original Cabernet Franc vines are almost twenty years old now and still producing well. Other wineries have tried some other varietals. We tried a little Merlot and can ripen it here, but one severe winter, we lost most of those vines. We also have a few hundred vines of Lemberger in the ground, which usually just ends up getting blended.

What about the hybrids?

There are dozens upon dozens of hybrids that could be grown in Connecticut. They have a bit more durability in our climate. The challenge with hybrids is they lack known name recognition when you are trying to market your products. But they make some very good wines.

We’ve had the best success with Cayuga White, developed by Cornell and grown widely in the Finger Lakes. Vidal Blanc is one of our favorite hybrids, a very versatile, aromatic white wine. We have some Seyval Blanc, another of the old French-American hybrids. Some other wineries in the state plant Traminette, another Cornell hybrid. On the red side, a lot of other Connecticut wineries use St. Croix, a very durable grape from the Minnesota breeding program. Corot Noir is another Cornell hybrid that we’ve planted.

Can you talk a little more about the challenges growing these grapes?

The biggest challenges that I’ve experienced growing grapes are the extremes in weather we’ve had. Some of my worst vintages were in 2018, when we just had one of the wettest seasons we can ever remember. There was rain upon rain upon rain, which devastated our crop.

Usually, the Cayuga White and our Muscat Ottonel are the first grapes to harvest, in mid-to-late September. Then our Vidal and Cab Franc aren’t harvested until the end of October. So we’ve got close to a six-week harvest window, and by spreading it out over that length of time, we do our best to compensate for extremes in rainfall from year to year.

One of those bad winters when I had a lot of damage in the vineyard was, until then, a relatively mild winter. Then, around Valentine’s Day, we had one of those awful polar vortexes, where it goes from a mild winter to below-zero temperatures for three or four days. If the vines aren’t fully dormant, they’ll end up with winter injury. We’ve also had some late spring frosts…last year, around May 8th or 9th, I’m walking and seeing little ice pellets in the vineyard. It was an extraordinary event for early May. Yet, despite these climate challenges, we've been able to consistently craft quality wines.

What do you think extreme weather and climate change are going to do to Connecticut winemaking?

It will make it more challenging. When you're invested in a perennial crop, like a grape vine, you can be three or four years into it and then lose it because of one cold snap over a couple of days, and then you’ve got to start over. It’s not an annual crop, like pumpkins; you’re going to plant a new crop of pumpkins next year, anyway. But with a vineyard, I had three years into this Merlot, I was just about to harvest it, and then it’s dead. I’ve got to start from zero and wait another three years until I get a crop. Do you think I was going to plant Merlot again? No, I switched over to a couple different things, which I knew were going to be more durable. It was frustrating, because we can ripen it here; we’ve got the sun. But these unpredictable variations of either cold snaps or warm snaps are making it a challenge.

The other thing that’s on the horizon is invasive species. We’ve been dealing with them in other crops, but the frightening one for grape growers is the spotted lanternfly, which feeds on the sap from grape vines. It’s been a big headache in southeastern Pennsylvania vineyards, and if this becomes an issue here, we’ll go from a crop that we’ve been able to grow essentially insecticide-free to a crop that might be forced to have regular insecticide treatments.

What does the future of Connecticut wine look like for you?

We’re going to focus on doing a great job growing grapes — including planting some more Cab Franc — and emphasizing an authentic Connecticut agricultural experience. I do think that people are becoming more appreciative of the work we do, because if there’s something that you don’t want to outsource, it’s where your food is coming from. I think people recognize that we have to do more to take care of our planet, and treating the land with care and respect is a big part of that.