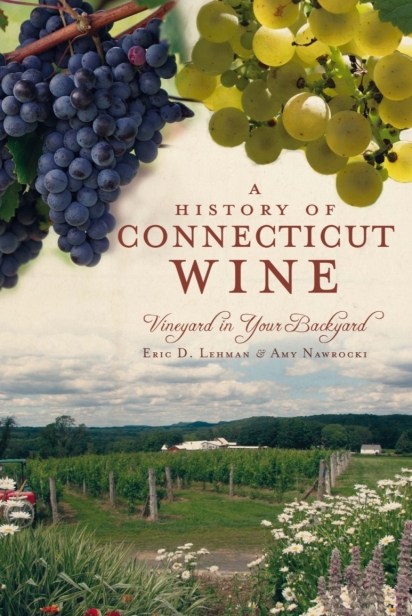

The Deep Roots of Connecticut Wine

When people talk about wine in Connecticut, they usually begin with several misconceptions. The first is that the state is not and has never been a “wine region.” The second and related issue is that the Puritans who settled the area did not drink alcohol. The third is that good wines can only be made in a Mediterranean climatic region, such as Italy or California. All of these are 20th-century conceits and, as we will see, demonstrably false.

Amongst the very few possessions that the English Puritans who settled New England could fit into the small holds of the tiny ships that brought them across the Atlantic was a “good Claret wine.” When colonists explored the new territories, the red and white grapes they found “gathered from thick vines edging the woods of every colony” were quickly fermented and turned into alcohol. The 1639 grape vine seal of the Saybrook settlement was chosen for the shield of the Connecticut Colony in 1665 as a symbol of good luck, felicity, peace, and acknowledgement of the state’s most plentiful fruit.

In the 1700s, a booming trade brought in Madeira, Port, Sack, and cream sherry for purchase at gathering places, like the Oliver White Tavern in Bolton. Apple orchards multiplied throughout the state, and families began to drink hard cider with every meal. However, by the turn of the century, workers in the new industrial factories acquired the strange habit of drinking coffee on their lunch break rather than alcohol, and fewer people produced their own wine. In the 1800s, the idea of temperance became more popular, contributing to a lack of winemaking and to an emerging notion that New England was “dry.”

But vineyards and wineries did not disappear entirely. In Bridgeport, a large vineyard was “flourishing” in 1827, and a year later, the Norwich Courier encouraged farmers to plant grapes, since “a good crop may be expected every year; besides the juice of the grape will improve by age.” By 1858, it was said that “the culture of the grape and the manufacture of wine or rather syrup from our native grapes, is beginning to be a source of remunerative employment in Connecticut.” Enough farmers were growing both American and European grapes to stage a Grape Growers and Vintners’ Convention, which resolved to expose adulteration and fraudulent wine and continue to “make a pure article.” In 1860, 500 students at the Yale Scientific School attended a lecture on viniculture, and growers began holding regular meetings to discuss their methods. Vineyards sprang up in towns like Fairfield, Middlefield, Hamden, and Waterbury. At the 1876 centennial exhibition in Philadelphia, W.N. Barrett of West Haven and C.E.B. Hatch of Cornwall displayed grapes in Connecticut’s booth.

At the turn of the 20th century, Italian immigrants flooded the state, and winemaking increased tenfold. Along the Berlin Turnpike, “extensive vineyards” sprang up, and by 1919, the Hartford Courant stated, “It is impossible to ride any distance in this state without coming upon vineyards…the native wine product of Connecticut must be large.” But all that changed immediately with the passage of the 18th Amendment, prohibiting both production and sale of alcohol in the United States, and by 1922, vineyards had disappeared from the landscape. Winemaking was reduced to small, family-sized batches for four more decades.

Then, in 1974 Sherman Haight of Litchfield gave up sheep and beef cattle and began to grow European vinifera grapes, like Chardonnay and Riesling. Joined by Dr. Paul DiGrazia and Bill Hopkins, Haight lobbied the Connecticut State Legislature to allow growers of grapes to produce wine on farms. It worked, and with the signing of the Farm Wine Act by Governor Ella T. Grasso in 1978, Connecticut farmers began to bottle their first commercial wines.

These pioneers had little to go on when it came to deciding what to plant and how to care for it, since any previous wisdom had been lost to history. “We made a lot of mistakes in the beginning, but hopefully, we didn’t make too many twice,” says Haight. At Bill Hopkins’ former dairy farm, he planted mostly cold-friendly hybrids: Lambrusco, Aurora, Cayuga, and Seyval Blanc, before successfully growing old-world vinifera, like Chardonnay and Cabernet Franc. The molds and fungi that attack the grapes in this wetter climate had been solved by improved techniques and fungicides, a fact that allowed wine grapes to be grown in every state in America, including many with far less suitable climates than Connecticut’s.

The best white wines are made in climates more similar to Connecticut than to Australia, such as the cooler regions of France and the Rhine valley in Germany, although summers are hotter here than in, say, northern Burgundy. Chardonnay grows here (as it does practically everywhere), along with Riesling, Pinot Gris, and Cabernet Franc — the latter of which has thinner skin than its offspring, Cabernet Sauvignon, ripens early, and is much better suited to withstand cold winters. In Europe, it is often used for blending, but in the Litchfield Hills and nearby Hudson Valley, the soil grants Cab Franc more rounded flavors, with hints of vanilla and spice. Red grapes from central Europe, like Lemberger, Wurtenberg, and Dornfelder, also grow well here, finding our soil and climate more advantageous than the frigid, glacier-fed valleys of Austria and Hungary.

Hybrid grapes work even better — in reds, the peppery St. Croix, ripe berry Frontenac, and chocolate-finish Marechal Foch grapes take the lead, with Marquette and Chambourcin following close behind. Cayuga White works even better than its parent grape, Seyval Blanc, and Vidal Blanc is a crisp alternative. The list goes on and on — from Villard Blanc and Pinot Blanc to Chardonel and Traminette. The names might be unfamiliar to those of us accustomed to wine store monotony, but the resulting tastes of these choices make their own case for diversity in grape cultivation.

Indeed, the only grapes that don’t work here are those that need too many growing days, like Cabernet Sauvignon, or can’t handle unusual cold snaps, like Merlot. Furthermore, a grape like Chardonnay might do better here than in a place with too much sun. As Sherman Haight once put it, “the grapes struggle here, and that adds to the quality.”

As far as managing that quality, the first authorized wine appellation in Connecticut was the Southeastern New England American Viticultural Area (AVA) in 1984, and four years later, the Western Connecticut Highlands was also designated an AVA, mostly thanks to a three-year effort by Bill Hopkins. He proved that the glacial schist and granite hills that included all of Litchfield and parts of Fairfield, New Haven, and Hartford counties (an area twice the size of Napa County) constitutes a “distinctive land area.” “We’re a little bit different than the rest of the state, climate-wise and topographically,” Hopkins says, “and you can’t use the words ‘estate-bottled’ unless you are from a viticultural area.”

Labels such as those matter to growers and consumers. Indeed, this attention to microclimate influence on viticulture resulted in the designation of a third AVA, The Eastern Connecticut Highlands, in 2019. Federal laws require 75% of a bottle’s constituent grapes to be grown in-state in order to be labeled a “Connecticut” wine, and 85% for an AVA designated label (representing one of the state’s specific growing areas). To be labeled “Estate-Grown” or “Estate-Bottled,” 100% of the grapes have to be grown not just in Connecticut, but also specifically on a single winery’s property within an AVA. It is a matter of pride for farmers and a matter of delight to consumers that our wine — Connecticut wine — has such high quality control. Connecticut’s high standards are all the more significant in light of our state’s small size. After all, a winery in San Diego can buy grapes from 500 miles away and still be called a California wine, whereas a Connecticut-labeled wine is, for the Connecticut wine drinker, truly a local product.

Summer is a season ripe with opportunities to visit our state’s vineyards, and with these misconceptions about Connecticut wine out of the way, you can get to the real joy – tasting the wine.