LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER

As of writing this, in the first week of November, my modest home garden is full of ripe, red, and delicious cherry tomatoes. The plants, themselves, are still vibrantly green. Were this early October, I’d simply be thankful that my plants had escaped blight or other fungal ailments brought on by an especially humid summer, but this is November, a time when Connecticut-grown tomatoes are traditionally in very short supply, primarily coming out of greenhouses.

Perhaps it is fitting, then, that today also brings across my desk the newly released Climate Science Special Report regarding the impact of anthropogenic activities on climate change. This report states that greenhouse gases from industry and, notably, agriculture, are the biggest contributors to climate change. To be certain, there are conflicting reports and opinions about industrial civilization’s role in climate change. However, what doesn’t seem to be in dispute is the nature of climate change, itself. According to the report, the past 115 years are “the warmest in the history of modern civilization.”

My personal experiences have verified this warming trend in action. During the years that I actively spent working at a diversified vegetable farm in Connecticut, the growing season appeared to shift. There were certainly anomalies – surprisingly early (and devastating) frosts or unusually cool, mid-summer weeks – but the overarching trend was always toward a late start to spring followed by a late start to winter. Towards the end of my farming experience, seasons were trending about a month later than traditional wisdom suggested they should. New England’s agricultural calendar appeared to be shifting. In fact, the 2012 update to the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map (which breaks the nation into different latitudinal farming regions based on average lowest winter temperature) indicates that all U.S. agricultural zones have shifted northward since 1990, some significantly.

It might be tempting to say, “So what? We’ll just have more tomatoes in November, and no tomatoes in July, right?” While that may be true (for now), the more disturbing thought that comes to my mind is what this may portend for agriculture in the future. Like all species, the plants that we depend on as a reliable source of food have evolved – either naturally or through selective domestication – to survive in a largely predictable, seasonally moderate climate. What will happen to them (and by extension, to us) if our climate continues to shift into a less predictable, less moderate status quo?

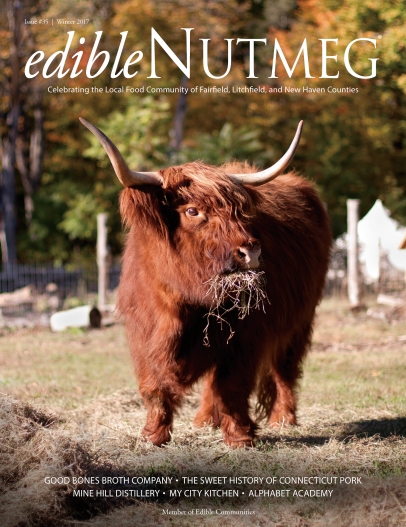

With causes that are disputed and solutions that are uncertain, climate change can feel like a daunting problem, but like any complex obstacle, incremental steps taken by many individuals can have a lasting and transformative impact. In this issue, we examine some of Connecticut’s excellent small-scale and sustainably-minded livestock farms. These hardworking farmers are slowly but surely helping to return our state’s animal farming landscape to one more closely resembling its traditional model: locally raised livestock living in natural conditions and requiring comparatively little carbon-emitting processing and transportation in order to make their way from the farm to your table. Even without considering the important ethical relationship that these farms engender with their animals, the markedly smaller carbon footprint that they produce in comparison to their industrial counterparts should be enough for us to take notice and take part. In some cases, traditional livestock farms may even serve to sequester carbon in the soil, rather than emit it. As the holiday season’s feasts begin in earnest, I hope that you’ll choose to learn about, visit, and purchase from our state’s small and sustainable livestock farms. Your holiday tables are certain to be richer for it, both now and in the future.