LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER

The humble chicken. It is a staple of agricultural civilization, with roots at least as far reaching. Although the origin of its domestication is debated, it is believed that it first arrived in Europe as long ago as 3000 B.C. and has since followed us around the globe. Valued for its nutritious eggs and savory meat, the chicken (when free to roam) is also a master of pest control; fleas, ticks, and other diminutive enemies of humanity are some of its favorite foods.

For these and other reasons, chickens have been an ally to and supporter of agricultural society as far back as we can measure, but as the industrial food engine of our modern world grows ever larger and more streamlined, we should ask, have we been as kind to the chicken in return?

It’s a question that applies to any animal that we raise for food, be it for dairy, eggs, or meat. In the less-mechanized agricultural world of our past, chickens and their domesticated kin lived what we can assume were comparatively enjoyable lives. They roamed open acreage, grazed and fed, and when the time came for slaughter, at least we could rest assured that they had lived well, having been protected, cared for, and sometimes even doted over.

These days, the word “slaughter” is frequently replaced by “processing,” a semantic attempt at softening the final step in our oftentimes far less humane modern farming system. Industrialized animal farms produce plentiful and inexpensive animal products, but the saved costs to the consumer come at the expense of the animals, who are commonly raised in dismal and deleterious conditions. And as the animals suffer, so too does our long-standing partnership with them.

However, here in Connecticut, we have ample opportunity to embrace an ethical relationship with chickens and other domesticated animals, even if we don’t raise them ourselves. Our state hosts an abundance of small farms that nurture animals in open, natural conditions, by farmers who care for their charges. If you visit them, many of these farmers will happily introduce you to their flocks and herds as proof of their commitment to ethical raising standards.

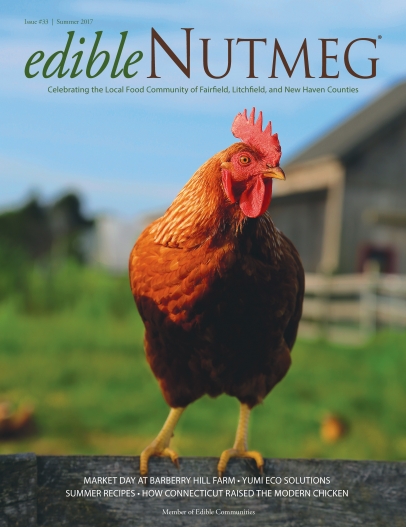

On such a visit, you might meet an animal like Gork, the rooster featured on our cover (from Back 40 Farm in Washington), who proudly preened and strutted along the length of the fence near where we stood, inviting us – no, begging us – to take his photograph. And in that, there’s a lesson: these animals should not be reduced merely to numbers on a “nutrition facts” label; they’re living, breathing creatures, rich with personality. In turn for the ultimate sacrifice they make for us, we owe them better than the miserable, caged existence that is fundamental to the inexpensive rearing methodologies practiced by our nation’s industrialized factory farms.

When we choose to buy animal products from our state’s sustainably and ethically minded farmers, we acknowledge that our relationship with the animals that sustain us is worth more than a few saved dollars, and that we are willing to sacrifice momentary convenience for the sake of their entire lives lived better. Through this, perhaps, we make ourselves deserving of the long history of assistance and sustenance offered to us by these animals.