The Chance Seedling

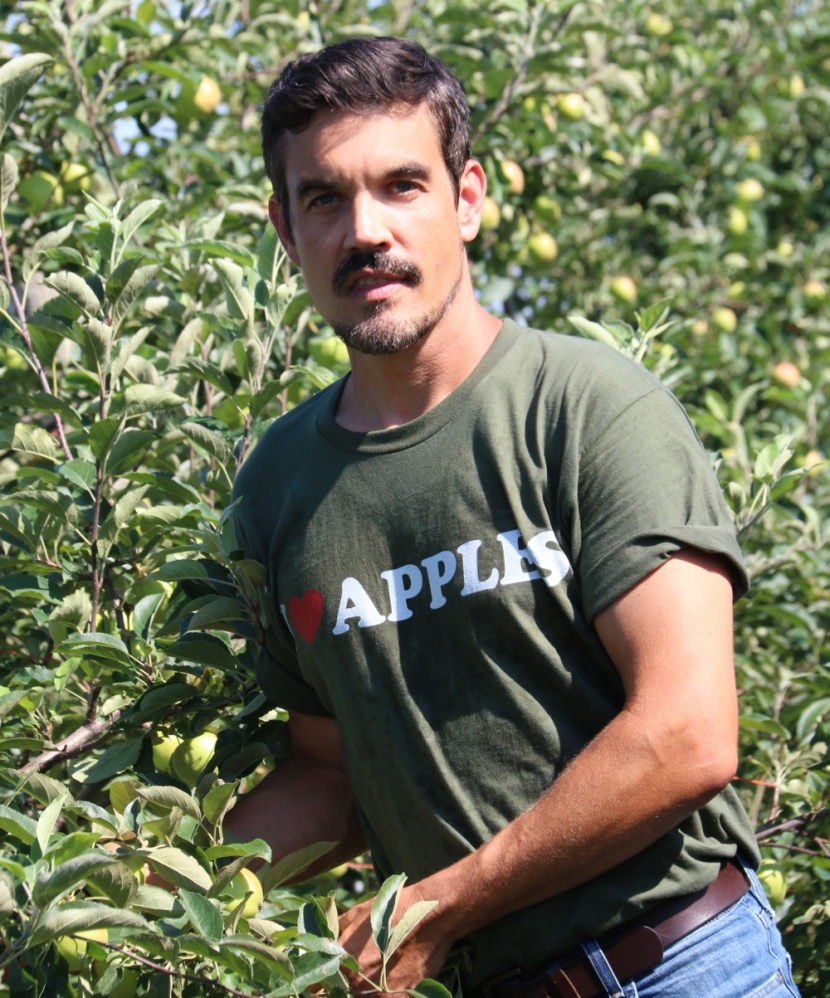

Established in 2017, Hidden Gem Orchard in Southbury is rooted in Wargo’s lifelong dream of owning a boutique orchard, cultivating rare and heirloom apples. A Woodbury native, Wargo’s passion for pomology (the science of fruit trees) has taken him from UConn to Cornell University to Australia, and eventually to Georgia where he started a family and a career as a research agronomist. But as the years passed, the call to return home grew as loud as his desire to start an orchard.

As a self-described Yankee, it’s fitting that Wargo’s orchard is not far from Yankee Drive on the Southbury Training School (STS) property. The school was established in 1940 by the Department of Developmental Services to operate as a residential facility for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Encompassing a sprawling 1,600 acres, STS once contained 125 buildings and was entirely self-sufficient, complete with housing and educational facilities for its residents as well as its own fire, ambulance, water, heating, sewage, and power services. However, with declining enrollment in recent years, much of the property has transitioned to other uses, and in 2016, stewardship of the land was transferred to the Department of Agriculture. With the aim of preserving farmland, the department opened areas for select individuals to obtain leases. Seeing an opportunity to pursue his dream, Wargo jumped on the application process. Soon, with the help of advisors, friends, and family, 30 acres sat in front of him, ready to be cultivated.

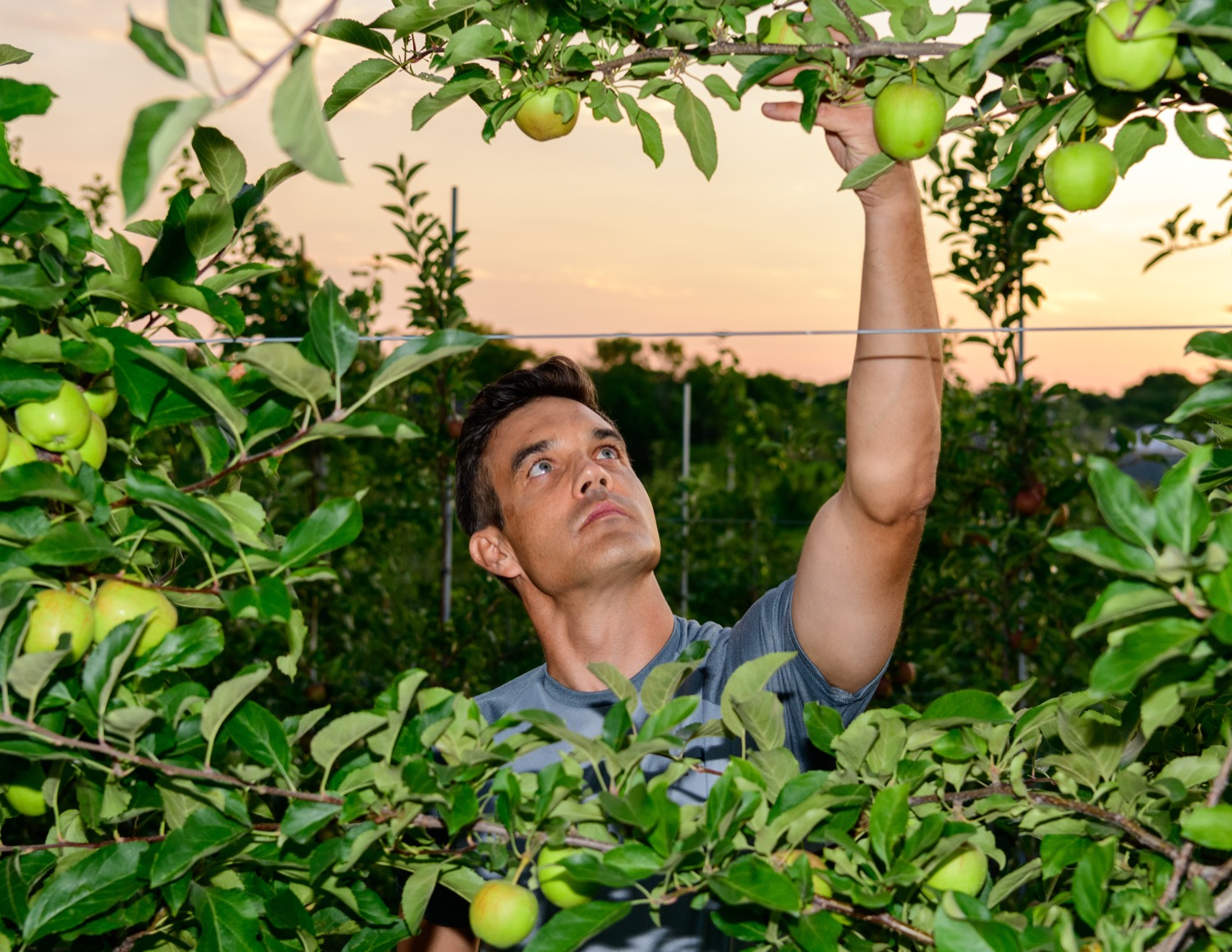

Flanked by grasslands and meadows thick with goldenrod and butterflies, around 4,000 apple trees now stand on a hill that was once part of an overgrown pasture. The rows of trees that weave across the two orchard blocks vary in size — from tall to short to wide to narrow — and bushy-bottomed trees laden with apples reach across the paths to leggy saplings, stretching high for sun, not yet heavy with fruit. Handwritten signs pegged to posts delineate the varieties. With rare and heirloom growing alongside modern favorites, a visitor could imagine they are reading a story where Rosalee and Baldwin sashay at a Gala in the Fuji Empire, attended by Pink Ladies in Pink Pearls on a Crimson Crisp evening with a Firecracker sunset.

There’s no definitive number of years that classify a crop as “heirloom” or “antique,” but most in the industry would agree that a variety should be at least 100 years old. One apple that Wargo grows, the Calville Blanc, dates back as far as 1598 and is prized in French baking as the essential apple for the tarte aux pommes. The Esopus Spitzenberg, discovered in the late 1700’s, was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson, whose plantings’ descendants are grown still today at his Monticello Estate. There are many reasons that some apple varieties may be more popular than others — flavor profile, appearance, texture, shelf life, cold weather hardiness, resistance to bruising (important for varieties that will be transported and handled a lot), and more — and Wargo works closely with his advisor and mentor, Ian Merwin from Cornell University, to select a wide range of apples with proven consumer appeal. Sometimes, he’ll try his luck on a variety that may be more difficult to grow, perhaps more finicky and particular, but if all goes well and his hard work pays off, “they’re just dynamite! If you’re willing to deal with the challenges, [they can be] fantastic.”

It’s safe to say his customers agree. “Apple connoisseurs,” as Wargo calls them, come from far and wide to visit his orchard in search of something different and unique, as Wargo specializes in hard-to-find varieties as well as heirlooms. Some visitors are just passing through, following a whisper of a recommendation they heard; others return every year and leave with bags brimming with apples. Cider makers are in luck, as well: a number of apples at Hidden Gem are chosen for specific qualities that are the essence of many craft ciders, with high sugar content and strong, distinct flavor.

Known as “chance seedlings,” many older cider varieties come from apple trees that developed naturally via open pollination, where, according to Nan Fischer from Nature’s Path Organic Foods, “the flowers are fertilized by bees, moths, birds, bats, and even the wind or rain, …[and the resulting trees are] genetically diverse, so there can be a lot of variation in the plants and fruits.” Many modern apple cultivars are, however, the result of intentional selection. Maintaining a connection with his alma mater, Wargo has access to some of the newest and rarest varieties from Cornell University’s apple breeding program (the oldest in the country). World renowned for its work, Cornell’s AgriTech apple breeding program is over 100 years old and has introduced 69 new apple varieties into the market. Through cross pollinating specific trees, researchers are able to amplify certain characteristics (such as pest and disease resistance, hardiness for specific climates, taste, and appearance) and develop varieties that meet the needs of today’s market. The process requires patience and time — some new varieties may take 20 to 30 years to develop — and sometimes, researchers have to just cross their fingers as they release a new variety to the public, unsure of how it will be received. Take the Firecracker, the latest from Cornell. Wargo took a chance on the variety, planting several trees in his orchard, and he’s glad he did. Dubbed a “triple threat,” Firecracker apples are unique in that their crisp firmness combines with an unrivaled balance of sweet and tart to make them perfect for baking, eating, and cider making.

In explaining his adoration of apples over other tree fruits, among many things, Wargo lauds their rich history and the role they’ve played in cultures throughout time, even earning a notorious place in the Bible with Adam and Eve. While modern apples’ lineage can be traced back to Central Asia, and many varieties grown today are of European heritage, apples have become a distinctly American icon: apple pies, The Big Apple, and the tale of Johnny Appleseed are all classic Americana. In her article “Who was Johnny Appleseed?,” author Mariel Synan explains that “cider was an essential at the American dinner table at the time, so most homes had their own small orchard.” At a time when drinking water was frequently unsafe, hard cider often accompanied meals and was enjoyed by young and old alike. Seeing a market ripe for the picking, the 19th-century horticulturist John “Johnny Appleseed” Chapman ensured apples were never out of reach by planting orchards along pioneer routes, selling travelers seedlings as they arrived to establish their new homesteads.

Wargo’s love of apples is apparent too in his choice of name for Hidden Gem Orchard. He wanted to impart a feeling of something unique and special, refined and perhaps reminiscent of a winery, a place geared more towards adults and small groups than the come-one-come-all “agritainment” vibe often found at other orchards (replete with corn mazes, face painting, and petting zoos). He’s proud of his apples, the result of hard and relentless work. They’re his “gems,” he says, smiling as he looks out across a dusty workshop to the thousands of trees dotting the hillside. He explains that the orchard of his dreams is “hidden,” out of the way, a place to be sought out by those who truly appreciate what he has to offer.

Being off the beaten path lends a tranquility to the orchard — until a loud “ka-BOOM!” punctures the air, and a cloud of crows lifts from the apple trees. Unfazed, Wargo explains: it’s just the propane cannon. Wargo faces challenges not unlike those of early settlers. Excessive rain, drought, wildlife, crop diseases, and pests constantly plague the fledgling orchard, causing crop losses and headaches as he labors over new management schemes. In 2018, Wargo’s second plantings suffered from torrential rains and poor drainage that drowned portions of the property; flash forward, and drought this summer has caused equal stress for the thirsty trees. While non-lethal wildlife deterrents are effective at first — like the propane cannons that detonate at regular intervals to scare birds, or wire cages around tree trunks to fend off rabbits — the animals are crafty and adapt quickly, leaving fruit pecked and tree bark damaged. But with the enthusiasm and excitement that Wargo has for his orchard, these challenges do little to dampen his positive outlook. He’s living his dream, he explains, and that’s what’s important to him. When asked if the hurdles ever make him second guess his endeavors, he explains that “this is the pursuit of an innate passion I’ve had my whole life, and I get to share that passion through the fruit that I sell to people. I take more satisfaction from the compliments I receive on my apples than I do from the money that the customer hands over to me.”

Limited only by the number of hours in a day, Wargo has embarked on a journey in an industry that many are leaving behind. The threat of climate change, rising costs of goods and materials, unreliable labor, changing consumer trends, and increased pressure from pests and disease prove a challenging set of hurdles for a younger generation of farmers. Yet, when faced with hardship, Wargo says it’s ok to feel frustrated and annoyed, and to take some time to sulk if needed. But he believes strongly in perseverance and the importance of getting back in the saddle to deal with the blows. After a recent hurricane ripped through his orchard and destroyed more than 50 of his trees, leaving a wake of debris, Wargo wasted no time in calling up friends: “I’ll bring the wings and beer, you bring your chainsaw!” Most people may not throw chainsaw parties, but after getting to know James Wargo, it quickly becomes clear that he and his Hidden Gem Orchard are anything but typical.

Hidden Gem’s farm stand will be open on weekends through Thanksgiving. For those who can’t make the trip to experience the orchard in person, select apples are also sold by other farms and in boutique grocery stores around Connecticut.

- Hidden Gem Orchard: 2500 Purchase Brook Rd., Southbury