The Rise and Fall of Connecticut Dairy Farming

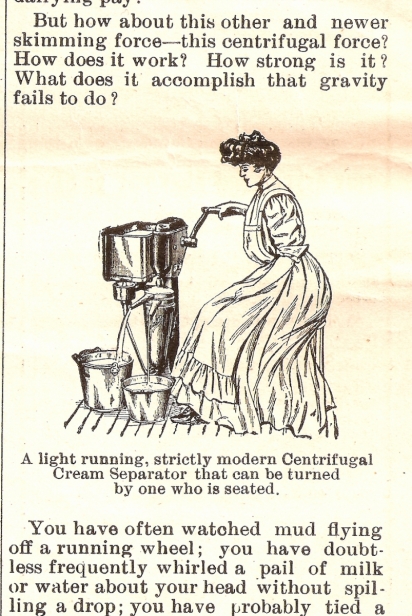

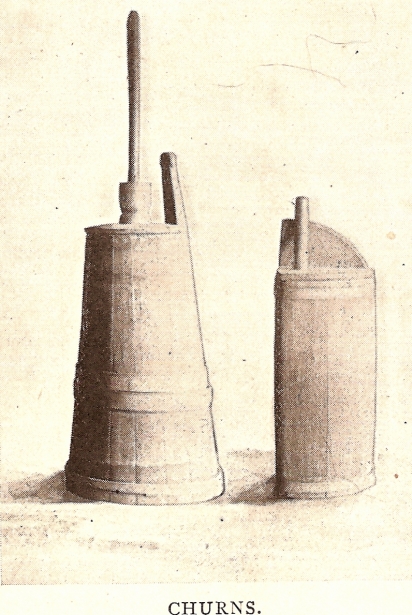

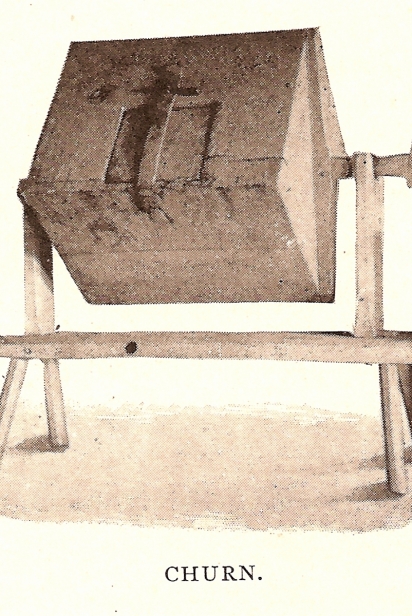

Dairy farming has been a part of Connecticut agriculture since Europeans first reached these shores. Once cows and goats arrived in farmyards in the 1600s, farmers milked them twice daily and churned that milk into butter or preserved it as cheese. The rest of this valuable liquid would be used immediately in cream sauces and in boiled milk porridge. Barns or houses would have a cool room called the “buttery,” and each family took pride in its one or two cows. Milk-producing animals were widespread, mostly as a means of basic sustenance.

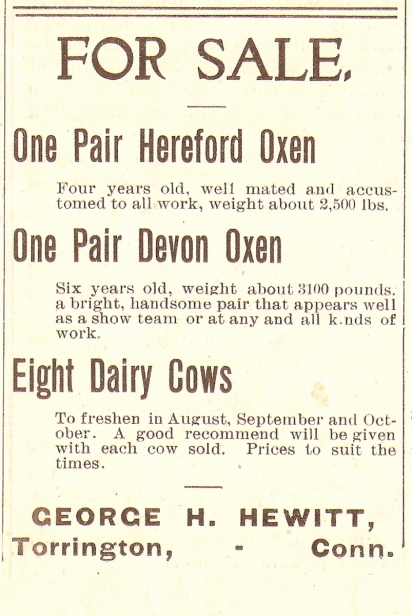

Butter and cheese were the methods by which dairy became commercially viable in those days, if barely. It wasn’t until the 19th century and the advent of railroads with refrigerated cars that milk could be sold beyond the local community. Cheese made it farther, and Connecticut farmers realized early on that specializing in this commodity was a way to compete with larger, western farms. In 1845, Litchfield County made two million pounds of cheese, renowned throughout America for its quality.

In the 20th century, refrigerated trucks and the interstate highway system allowed milk to be shipped, increasing its commercial value tenfold. By the 1950s dairy farming had become a sensible livelihood. New stall designs, artificial breeding, and better veterinary care increased milk production, and soon, more efficient dairies were producing twice the amount of milk they had been. Connecticut was a leader in this field, with our cows producing far more milk than the U.S. annual average.

This paradoxically led to more inequality between small and large farms, and then to consolidation. Fewer farms with more cows began to be the norm. Farmers stopped diversifying, throwing everything into this lucrative specialty. Farmers gave up their tobacco and corn for herds of these money-making beasts. A place like Kent, once full of farms of all sorts, became mostly dairy farms, sending their milk by train to New York City. By the mid-20th century, Connecticut was firmly a dairy state.

Today, little of that vast industry remains. So, what happened? Several things, all at once. The rise of huge factory farms (known as “mega-dairies”) in the western United States hurt, simply because they could afford to do business more cheaply. With an interstate highway system, people in New England could drink milk from Wyoming. Also, federally regulated milk prices do not take into account the higher costs of doing business in places like Connecticut. The low price of milk versus the high cost of equipment also meant that massive farms had better margins. Supermarket pricing wars contributed to the problem.

Real estate prices also rose in the late 20th century, causing residential development to boom. Western Connecticut was particularly vulnerable, since wealthy New Yorkers were buying up land for private estates at an astonishing rate. The short-term gain of selling land for development became too tempting for many struggling farmers. At the turn of the 20th century, there had been a hundred dairy farms in tiny Washington, Connecticut. By the end of that century, there were only two. Fewer farms meant less supporting infrastructure for the remaining ones, and a domino effect began.

America also experienced a general decline in milk consumption, partly driven by medical studies from the 1970s linking whole milk to heart disease, and partly by the rise of vegan alternatives like soy, nut, and oat milks. People began to drink more soft drinks and energy drinks, and for some, milk became little more than an additive to coffee. Demand for milk is over one-third less than it was 50 years ago, despite a higher population, and despite a higher volume of production. Even without federal regulations, that led to a low price that simply put smaller farms out of business. The number of dairy farms in America today is less than 10% of what it was in 1970, but those farms are producing more milk. Unfortunately, those mega-dairies often keep their cows in questionable conditions, feed them questionable diets, and pollute water and land far more than a collection of small farms ever did.

Yet, despite the great diminishment of the industry in our state, bright spots remain. The local food movement has helped to rekindle small-scale agriculture of all types throughout the state, including dairy farming operations. Although few in number, Connecticut’s farmstead creameries (using milk provided by their own herds) are becoming well known for their high-quality dairy products. Arethusa Farm (Litchfield), Thorncrest Farm (Goshen), Calf and Clover Creamery (Cornwall Bridge), Cato Corner (Colchester), and Shaggy Coos Farm & Creamery (Easton) all produce fresh milk or cheese from their own ethically raised and managed herds, just to name a few.

In addition to producing local food that is both nutritious and delicious, these small dairies operate as animal stewards, treating their herds with respect and care — a claim that cannot generally be shared by industrial dairy farms. Their herds help fulfill a restorative niche as grass grazers who manure the fields and enrich our agricultural soil, all the while providing employment for the people who tend them, as well as those who process, transport, and sell the dairy products that are made with their milk

Small-scale dairy farms bring resiliency to our food network by providing nourishing food produced in our proverbial backyards, resiliency to our environment by helping restore soil health, and resiliency to our communities by providing employment to the people who manage them. Their loss and slow revival should serve as a cautionary tale, reminding us that supporting our local food producers isn’t just good for them — it’s good for us, too.