Making a Hash of It

Sustainable eating for the future means careful planning by farmers, consumers, and communities. One of the major challenges is not food production, but rather food waste at all levels, from the farms to the grocery stores to the dinner table. The United Nations estimates that a third of food produced for humans never gets eaten. This amount of waste constitutes an environmental, economic, and ethical problem.

Our New England ancestors lived in a world in which wasting food was an even more serious thing – potentially endangering a family’s food supply – and therefore was carefully avoided. Necessity is the mother of invention, and they had many strategies to help mitigate food waste. The flexibility of dishes is one thing that helped – “Oh, we have salt cod instead of salt pork, just use that instead.” One reason there were few precise recipes in early America was the uncertainty of available ingredients. The doubtful preservation options, too (particularly in seasonal Connecticut), meant that leftovers had to be quickly eaten or thrown out, regardless of what the recipe might normally call for. So New Englanders gathered what was going to go bad first, adapted their family recipes, and made a new dish. This is how many global recipes became popular, from curries to hot pots to chowders. Small quantities of meat or one lonely egg might seem useless; added to a stir fry or a soup, they blend in. Stale bread becomes stuffing for the pheasant, and the giblets go into the stew pan. Many dishes developed to repurpose leftovers, chopped up and blended in with a delicious sauce or spice.

Getting reacquainted with these combination dishes is one way to diminish waste in our kitchens, as well as our budgets. We can vacuum seal or pickle fresh food, and we can keep a well-stocked cupboard and freezer with canned, dried, or frozen staples that are easily mixed with leftovers of various sorts. We can heat up the wok and break out the stew ladles. It only requires a more-mindful relationship to our kitchen and our food.

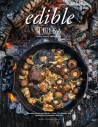

One of the most popular Connecticut leftover solutions was a “hash,” a mixture of chopped-up meat and potatoes, browned in a skillet. In her Domestic Receipts Book, Catharine Beecher commented that “a good hash is not only a favorite dish in most families but an essential article of economy and convenience.” For a long time, one of the most popular was red flannel hash. The “red” in this dish comes from beets, which became one of the most prevalent crops in the region from the 1700s through the end of the 1800s. Beets kept well in a cool basement for months, and so were nearly always available. Mixed in with brisket, turnips, and onions, their juices turned everything in the dish a purplish red. This coloration visually combined disparate ingredients, disguising the fact that we were actually just eating last night’s scraps.

As economies grew and refrigeration methods improved, so did our laziness and fanaticism for things new, fresh, and different. Dishes like red flannel hash became unnecessarily associated with cheapness and nostalgia, though they luckily found their way to diners across the country. But we can’t expect restaurants to solve problems of wastefulness. If you take food home from the bistro or grocery store, eat all of it. It doesn’t take too much extra effort to reinvent leftovers.

The great thing about hash is its versatility, and a recipe can be adjusted for serving size and varied ingredients. While corned beef is traditional, try pork or fish, or ditch the meat altogether and supplement potatoes with turnips, parsnips, and carrots. Homemade pickled beets add acid and a pungent kick.