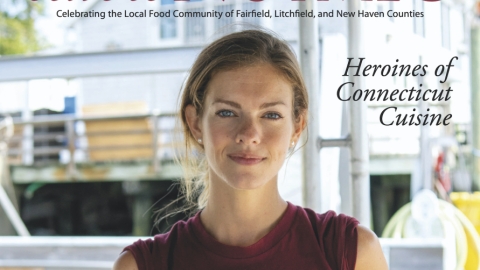

Ebb & Flow

You know you're doing a good job when “Lobster Mike” tells you he's impressed. Being the last man standing in a dying industry can make a guy a little gruff, to say the least. Watching me dig around like a raccoon in a tub, black with mud, fishing out sea squirts with bare hands, he chuckled to himself, saying I was really “somethin' else,” as he trudged away. Later that week, when I told him I was on my way to meet with a senator about ocean conservation legislation, he shared that, while I may not know it, I'm setting the groundwork for a great future for myself.

It doesn't always feel like that, I told him.

“Stick around, kid, and you're gonna go far.”

This isn't at all what I envisioned for myself, three years earlier, as I packed my Manhattan apartment into the back of an old Bronco, having quit my job as a wedding planner and given the boot to a guy who called himself my boyfriend. Frankly, I had no idea where I was headed. I was driving home to Connecticut to start a job I’d found on Craigslist: working as a deckhand aboard an oyster boat.

The next morning, I slept through my alarm and missed the boat on the first day of my new life. I called my ex-boyfriend sobbing, and quickly remembered why I'd just dumped him. Now what?

Turns out, in the oyster industry, you get a few strikes before you're out. With the help of three alarms, I soon became a morning person – three alarms and arriving at work half an hour early every day to doze lightly in my car until the rest of the crew arrived, all so I could tick off one of the few job qualifications: I could show up on time. It was clear that my college degree and polished resumé weren't going to come in handy, at least not for the time being, but the ability to get down and dirty, which I'd picked up from working on farms and construction sites, shone through in my first few months aboard the Paige Lane in Stamford, Connecticut.

Carting totes of oysters down the dock one rainy morning in the thick of my first winter season, the only other American crew member turned to me, as we paused to catch our breath. He told me how none of the guys had expected me to stick it out; they thought, surely, I'd have jumped ship – maybe literally – by that point. “But, you just keep showing up,” he said, a little smile beneath the shadow of his dripping hood. I was the only woman (affectionately nicknamed “Princesa”), barely spoke a lick of Spanish, and weighed about as much as the hose I dragged around the deck all day, blasting shells and muck overboard. But I kept showing up.

Three years and four companies later, I'm still handy with a hose, but I've added to my skillset: I'm now proficient in questionable Spanish slang, can nearly tolerate the smell of oyster shells baking in the summer sun, and can sport a pair of orange Grundéns overalls like I'm at New York Fashion Week. Every day is a little different where I currently work, at Norm Bloom & Son’s Copps Island Oysters, and because of that, I've become a Jill-of-all-trades. The spring and summer months are dominated by the oyster nursery, where millions of babies, or “seed,” demand my attention six days a week, making me the Oyster Mama. When waters are brimming with food, they pop from the size of a grain of sand to over an inch in less than six weeks, needing constant maintenance. Daily cleaning of over seven million oysters requires patience and podcasts, and an affinity for muck is a must. While friends are counting steps, I'm counting barrels – barrels to haul, to scrub and scoop, to rinse and repeat.

The long weeks of labor are broken up by time in the office fulfilling orders and keeping on top of paperwork. I lead farm tours for visitors, taking them through the life of an oyster, beginning at my nursery and ending at the retail shop, and I link up with our resident marine scientist to monitor local water quality, boating by my first boyfriend's childhood home, my high school rowing club's boat yard (that's long since been replaced by a drab office building), and on some days, my beloved Paige Lane. We take samples to be tested in our lab, we document the vitals – salinity, dissolved oxygen, temperature, turbidity – and most importantly, we watch. We watch for changes, for disturbances and the out-of-the-ordinary. We watch flocks of cormorants feast as flounder populations disappear. We watch coastal communities develop, ebb and flow, and grow and grow and grow.

Thursdays, I scrub up and head to town, oysters and clams in tow. At the Westport farmers market, I pack my fully-grown babies, harvested locally that very morning, into cooler bags for buyers at a dollar apiece, all of which is donated to local charities. Westport is my hometown, and this market is rich with memories for me. We share our summer lot with the fair I looked forward to all year as a kid, where I'd bake in the sun for three days standing in line for rides and waving to friends from atop the Ferris wheel. In the winter, the market moves down the road to Gilbertie's Herb and Garden Center, where my interest in growing food began. I spent every summer in college working at Gilbertie's, and when asked what my job was, I would give myself an impressive array of titles: Organic Hydration Specialist, Water Distribution Manager, or Lead Irrigation Technician. When you spend your college summers as “the water girl,” alone in greenhouses, soggy shoes burping as you pad between rows of tomato plants, you get a little creative.

Some days, I dress to impress. If I stop by the oyster farm in a fresh black button-up and my cleanest pair of pants, it means I’m on my way to a shucking gig. Drawing on my city days, I’ve combined my experience in event production and my ability to crack open shellfish with finesse to create Precious Oysters, a “tide-to-table” shucking service. What began as opening a few dozen oysters for friends’ dinner parties has grown to gigs at festivals with thousands of attendees, high-profile fundraisers in New York City, and even private events for local celebrities. What remains the same throughout my events, regardless of the occasion, is an authentic connection to what I’m serving. Watch me shuck, and you’ll learn the life cycle of an oyster, the story of the recovery of the Long Island Sound, and what happens to the shells in my Shell Recycling bucket. I explain the myth of the “R” rule and the secret to the perfect mignonette while adjusting the fresh seaweed framing my ice display.

My friend, Steve “The Shucker,” once told me that oysters meet your eyes before your belly: presentation is key. And while speed is necessary, it’s not the focus – not for my events, at least. That’s for the restaurant kitchen. If it’s possible to be a spoiled shucker, I’m guilty. I can crank through several hundred beefy Copps Island oysters smoothly, thanks to their sturdy shells that don’t mind a little rough housing. But when handed a ticket for a dozen delicate Aunt Dotties, I’m reminded that I’m not yet an expert shucker.

Working in a Westport seafood restaurant kitchen has given me yet another perspective on the life I’m living as an “oysterette,” a name Lobster Mike barks at me when our paths cross. There’s a sense of pride I feel when ducking into a walk-in fridge and seeing the tag that I’d printed that morning sticking out of a bin from Copps. But there’s also a sense of community, seeing my comrades’ boxes of fresh produce at the farmers market, catching my friend from catering, ushering guests to their tables, and watching my company’s motto, “tide-to-table,” in action, not at a private event, but for co-workers digging into happy hour, or a couple on a first date, finding common ground.

Mike was right, in a way. I am going far - without even leaving my hometown.