Waldingfield Farm Gives Insight Into the Changing Landscape of Organic Agriculture

28 Seasons Later

In the winter months leading up to the 2017 growing season, the classically colored red barn at Waldingfield Farm stands out against the muted landscape of the property in Washington, Connecticut. Most of the 20 acres of cropland remains dormant, with some signs of winter greenery staying warm under blanket-like row cover within the farm’s sheltered growing tunnels. Inside the barn’s office, farmer-owners Patrick and Quincy Horan and farm managers Jed Borken and Will O’Meara brainstorm for the season ahead: crop and field planning, assessing farmers market sales, and refining their community supported agriculture (CSA) program. Now entering its 28th season, Waldingfield Farm (a Bay State-certified organic farm) and its farmers have seen marked changes both in the business and in the greater local and organic food movements.

Growing Food; Growing a Business

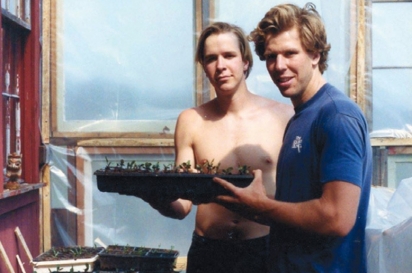

In 1990, Patrick and Quincy’s older brother, Daniel, armed with a working knowledge of organics and small-scale growing (along with the muscle of his younger brothers), started working their family’s land for vegetable production. He began on a half-acre plot with an ambitious goal of having a 15-member CSA program in the first year. He embraced organic growing standards, a concept that was then new to friends and neighbors.

“When Dave Blyn [of Riverbank Farm] and my brother, Dan, started, you would have been stunned by what people thought organic farmers were doing,” Patrick says. “The assumption was that organic farmers were a bunch of Grateful Dead fans who couldn’t balance a checkbook. But even back then, it was a real business.”

Since then, Waldingfield has grown incrementally and notably but has remained true to its organic-growing roots. It shifted from its early days of heirloom tomato-centric crop production and now offers a diverse range of vegetables, heirloom apples, and a popular valueadded food product line, including sauces, maple syrup, and their sought-after Bloody Mary mix. The CSA program has also grown and currently boasts the capacity for 200 member shares.

The Changing Marketplace for Organics

Although the philosophy behind organic farming has changed very little over its history, the marketplace for organic products most certainly has, and in some cases, consumer conceptions of it have not kept pace with economic realities.

Customers tend to assume that organic produce will carry a significant surcharge, though costs today are getting ever closer to the prices of conventionally, locally grown food. “In 1990, the price of a bunch of organic arugula at the New Milford Farmers Market was $2.75. It is $3.00 for the same amount today. Less than a penny per year it’s gone up, not keeping pace with inflation,” says Patrick. “The market for local food has caught up with organics to the point where there’s very little price difference between conventional-local and organic- local.”

This is the result of the rapid growth of consumer interest in local and organic food and in spite of the increased number of growers and producers in that marketplace. There are 48 certified organic farm operations in Connecticut and an additional 119 agricultural businesses that participate in CT NOFA’s Farmer’s Pledge program, in which farmers promise to adhere to organic growing standards but are not tested or certified.

As the organic industry has grown, competition within it has occasionally led to controversy, despite the common interest that all small-scale farmers have in promoting local agriculture. "One of the things that organics has had to come to terms with is, why do we have to label but conventional guys don't?" says Patrick. “It’s tough to understand, because organic produce is the starting point, really, and it’s conventional produce that has inputs and additives that would demand some sort of informational label. But we’re into farming, first and foremost, and want to see small-scale agriculture succeed. It's counterproductive for us to disparage another farm, even if their growing philosophy is different from ours.”

The Horan brothers welcome the friendly competition – especially if it can lead to an increase in statewide agricultural production – but the shrinking price gap between conventional and organic produce creates a marketplace environment that demands greater food literacy from a consumer base that has historically used price points as a primary decision basis.

As part of their effort to increase consumer awareness, the Waldingfield team uses its marketing tools for advocacy and education, from witty and informative signs at farmers market booths, to onfarm events, to regular blog posts and newsletters that highlight both the benefits and challenges of organic farming. The use of social media has also been a boon for the farm, allowing Waldingfield to effectively communicate with consumers and receive feedback from its community.

The Role of Community

Patrick underscores the value of staying engaged in that community and ensuring that the farm and its crew maintain an active presence in the local landscape. “I want people to think of us as an important aspect of their community and a part of their lives. As agriculture moves from the national to the local market, it is shifting from being a simple, vendor transaction at a grocery store to being something participatory, like joining the local YMCA or joining the library. It’s something that the consumer needs to have a role and a voice in.”

“We have to fight for organics every day, and we have to do it collectively,” says Patrick. “We want the consumer to know that Waldingfield is a synthetic-free, chemical-free environment, but ultimately, the onus is on them to be involved. Ask us any question. Come to our farm. Come see what organic food looks like. Organic farming only works when the customer is interested in knowing where and how their food is grown.”

Cultivating A Forward-Thinking Farm Plan

Organic farming has seen significant shifts since its humble beginnings, both in increased marketplace acceptance and community support, but it now faces a new challenge that will test the entirety of the industry, organic or otherwise, as farms are increasingly managed by aging owners and staff who find few young farmers with whom to share their knowledge and experience.

The latest U.S. Census of Agriculture indicates that the average age of primary farm operators, both nationally and in Connecticut, is 58 years old. While younger than this average, the Horan brothers want to ensure the preservation of Waldingfield’s infrastructure and philosophy for future generations. “One of the things that I’ve started to focus on and take note of is the value of young talent,” says Patrick. “The farm benefits from the help of young, novice farmers, but the work provides invaluable knowledge and experience for them. Many of our previous farmhands have gone on to become skilled laborers and managers within the organic agricultural industry. These new farmers are bringing an ability to articulate not just agricultural but also cultural and economic ideas. They’re thinking about the direct effect that their business is going to have on their region,” says Patrick.

Although Patrick and Quincy remain at the farm’s helm, they currently share its operational responsibilities with year-round managers Borken and O’Meara, both of whom share in the spirit of the farm, as well as the work load.

Farm Manager Jed Borken took a circuitous route to organic farming. He joined the team at Waldingfield in 2010 after a career in law. When asked about what attracted him to farm life, Borken says it’s about the bigger picture. “Leading a purpose-driven life is very important to me. It’s hard to argue that there’s any greater purpose for your life than to grow food for your family, your friends, and your community,” says Borken. “For me, personally, that’s where I get the most satisfaction.”

Assistant Farm Manager Will O’Meara began working at Waldingfield during his junior year of high school and eventually went on to UMass Amherst and its Stockbridge School of Agriculture, graduating in 2016 and returning to Waldingfield. For O’Meara, agricultural work is much more than a paycheck. “I think farming like we do is a bit of an act of resistance. Not a big one – we’re not putting our lives on the line or anything like that,” says O’Meara. “But if this past year in politics tells us anything, it’s that investing in our local community and in our state and in our region is incredibly important, if we’re going to be resilient and self-sufficient, in spite of what’s going on nationally. I think that farms are just one of the great ways to strengthen our smaller communities.”

“We couldn’t run our farm without them,” Quincy says of the team of managers and farmhands who perform the majority of daily tasks in the field. “And to have a crew that shares the ideals my brothers and I had when we started this farm means that this project will keep on going.”

As local and organic farming continues to grow and develop, the insight of experienced farmers helps to highlight the issues and complexities that lie behind the comparatively simple act of putting healthy food on our tables. Farmers like those from Waldingfield helped build the organic farming movement in America and have gone on to become champions of not only the environmental primacy of growing organically, but also the importance of agriculture’s role in our communities and how we might extend it for future generations. Their 28 years of experience offer a window into how the organic industry has changed and what it will require to keep it moving forward.

Waldingfield Farm

24 East St., Washington

860-868-7270