The Seed Huntress

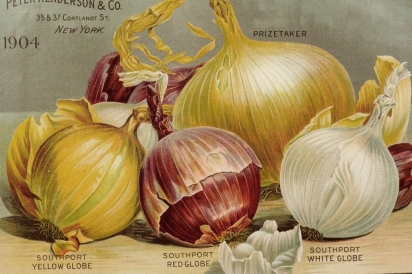

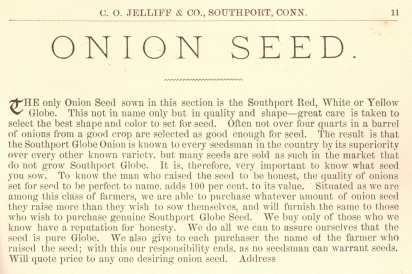

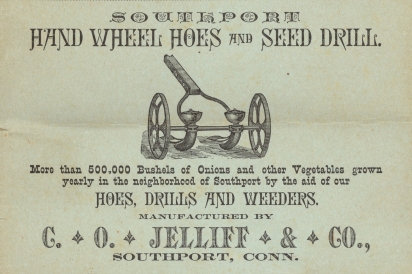

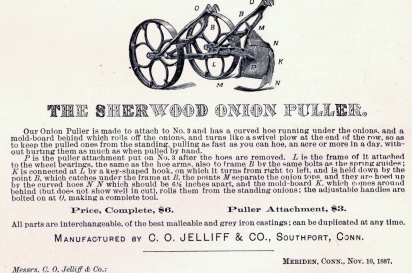

Marked by waterfront homes, a yacht club, and golf course, Southport is rarely thought of as seedy. However, in its early days, Southport was deeply indebted to the gift of seeds and one particular seed among them: the Southport Globe Onion. Often forgotten today, the onion was a regional staple that brought global renown to Southport in the mid- to late-1800s, a fact that local resident Sefra Alexandra – known to some as The Seed Huntress – hopes to change by restoring this heirloom crop to prominence. A Cornell-educated ethnobotanist and resident of the Greens Farms neighborhood of Westport, Sefra is working to revive both the regional onion culture and the Southport Globe Onion seeds that initially brought wealth to the area. She envisions the project as a way not only to remind residents of their roots, but also to maintain a living history and restore much-needed biodiversity.

Sefra’s first step was to collect some of the heirloom seeds and get them into the ground. She approached The Connecticut Audubon Society with an appeal for growing space at their new, native plant restoration site and was rewarded by board members with two garden patches in Southport – one each for two of the famous onion’s varieties: the Southport White Globe and the Southport Red Globe. What then started this past spring as the simple planting of onion seedlings quickly grew into something bigger, as residents took notice. Interaction with curious locals began adding depth to the project, as Sefra uncovered a trove of oral and written history. “I was able to get Audubon excited, but then came the stories,” she says. “People would tell me ‘this used to be an onion field,’ or ‘my grandfather captained the sloop.’ All the oldest families in this area were onion people.

These family agricultural histories are intertwined with national history. At peak production during the Civil War, 200,000 barrels of Southport’s onion harvest were shipped on sloops from Southport Harbor to New York City every year. There, they were often purchased by the United States government to feed soldiers. The Southport onions were known for their long shelf life, rich color, healing properties, and – perhaps most importantly – their ability to ward off scurvy.

This exploration of the Southport Globe Onion’s history has provided Sefra with a wealth of information and traditional practices, some of which she has put to use. For instance, eschewing contemporary growing methodologies, Sefra and friends canoed into the Long Island Sound to gather seaweed and algae for use as both mulch and fertilizer, a time-honored tradition that goes back to the region’s first onion farmers. Since onions produce seeds biennially, Sefra will harvest the onions this fall and place them in cold storage. Next spring, they will be replanted, and during that time will grow puffs of white flowers from a spherical umbrel, a cluster of flower stems that grow from a single stalk. Once the umbrels wither and desiccate, the flower heads will be removed and the seeds will be harvested. That act will be a definitive moment for the project and the region. “These will be the first Southport Globe Onion seeds grown in Southport in 130 years,” Sefra says.

However, planting and harvesting the Southport Globe Onion is only one part of Sefra’s larger Southport Globe Onion Initiative. In an effort to expand seed diversity, she created a seed library at the Pequot Library in Southport by converting an old card catalog, adding packets of seeds, and providing a log for those who would like to “check out” seeds. The borrower then “returns” seeds to the library when the crop reproduces, ultimately resulting in a bioregional seed hub of plants specifically proven to succeed in the local terroir.

Sefra envisions additional extensions of the initiative, including a Southport Onion Festival where local chefs would work with the seasonal onion harvest. She also wants to engage area students in the initiative as a way to mentor young people about the region’s traditional knowledge and cultural heritage. As a certified permaculture design educator with an M.A.T in agricultural education, she knows it will serve as a way to connect students with the outdoors and spark an interest in nature. “I want to put the ‘farm’ back in Greens Farm,” she says, noting opportunities to engage young people throughout the school system. “There is already a successful community garden located behind Long Lots Elementary, and I want to involve the students at Staples [High School].” Sefra points to Bridgeport’s Green Village Initiative – where she had previously helped implement school gardens – as an example of what can come from a program like this. “Every single kid there gets this innate joy from working with the soil,” she says. “It creates a deep connection to nature that fuels all this goodness.

Although Sefra approaches all aspects of her project from a point of positivity, she remains a scientist, clearly cognizant of the challenges confronting humanity, and what role a humble onion might play in them. She cites climate change but also the lack of both seed diversity and food security as dangerous factors that could potentially contribute to food instability in any city or town, including Southport. All of this makes it imperative to restore and maintain seed diversity, which has steeply declined in recent decades. “As the climate changes, we don’t know which traits and seed varieties will be best able to adapt and survive,” she explains. Sefra’s perspective stems partially from her time spent in Puerto Rico and Haiti, helping rebuild seed stores after Hurricane Maria’s and Hurricane Matthew’s devastating and deadly effects. “[But] it doesn’t have to be a natural disaster,” she says. “In any agrarian society, maintaining vast biodiversity is extremely important. You must have seeds from different microclimates. You never know which strain will withstand whatever climate situation you may face. Diversity is resilience.” She also believes that seeds can be an antidote to the “doom and gloom” that climate change news inevitably carries. “Seeds are a party,” Sefra says. “You become part of a movement by saving and sharing these little gems, hidden in every fruit and vegetable we eat.”

Besides her multi-layered initiative in Southport, Sefra serves as a Genebank Impacts Fellow at The Global Crop Diversity Trust. As a part of that work, she spends time in Fiji, studying the effects of climate change on taro, a root crop that is central to the nation’s culture and a key regional food source. And though she often carries her work abroad, far from her beloved Southport Globe Onions, the cultural seeds she has sown here in Connecticut are already starting to come to fruition. She hopes that her work encourages people to plant our state’s historic onion as a reminder of both Southport’s and Connecticut’s heritage. “After all,” she says, “the onions really want to come home.”

> Learn more about Sefra Alexandra’s projects at SeedHuntress.com.