Guaranteed Sweetness: How to Find Real Honey and Avoid "Funny Honey" Business

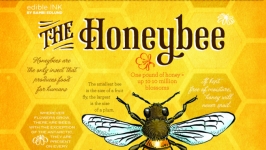

Embraced by many recent diet and health trends and revered for its flavor, honey shows no sign of stepping aside as the darling of natural sweeteners. It’s something that Americans eat a lot of: total U.S. honey consumption reached 517.8 million pounds or, roughly, 1.61 pounds per person, according to the 2016 U.S. Honey Industry Report.

In recent years, consumer demand for honey is outpacing what domestic beekeepers and apiaries can produce. The U.S. honey market sources significant amounts of imported honey from Canada, Argentina, Brazil, India, China, and Vietnam, according to the December 2017 National Honey Report from the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service. The downside to this increased popularity is the proliferation of “funny honey,” or honey that has been adulterated or mixed with cheaper sweeteners like high fructose corn syrup, sugar water, water, and, in extreme cases, chemicals. It can also refer to honey that has been illegally trafficked and traded.

The Honeybee Conservancy, a non-profit organization dedicated to improving bee welfare, estimates that about 70% of honey on U.S. grocery store shelves is adulterated. Testing for adulterated honey requires sending samples to specialized labs, which can be cost prohibitive for consumers. Making matters murkier are the myriad labels found on honey bottles – like “natural,” “raw,” “unfiltered,” “pure,” and “real” – that are not regulated by the FDA and could be used by any producer without investigation or enforcement, making them largely meaningless. “Organic” also remains an elusive concept in the honey market because bees often travel several or more miles to forage nectar, a distance that is typically outside of an apiary’s boundaries and property management practices.

Thankfully, however, there is good news in the midst of this not-so-sweet situation: great, unadulterated and largely unprocessed honey does exist, and finding it in the marketplace is possible, especially if you keep in mind the following insights:

Look for crystallization

Sight alone cannot tell you if a bottle of honey is adulterated, but it can be a good indicator of the manner in which it was processed. “When you look at a bottle of a beekeeper’s honey, it should be fairly foggy, because foggy honey has pollen in it, and commercial honey is usually very transparent,” suggests Carla Marina Marchese, owner, beekeeper, and resident honey sommelier of Weston-based Red Bee Honey. This fogginess is a sign of crystallization, a naturally occurring chemical process caused by the interaction of temperature changes, the ratio of sugars (glucose and fructose) in the honey, and pollen.

The more transparent, runny texture seen in many popular, less-expensive honey brands is often a result of honey that was heated during processing. “Once the honey is heated, it is put through a high-pressure filter, straining out pollen and wax particles so that it is more eye appealing,” says Mike Rice, beekeeper and owner of Mike’s Beehives in Roxbury. When larger honey packagers import barrels of honey from other countries, they must heat and pasteurize the product, because honeybees are considered livestock by the USDA, and honey is a by-product of an animal. Many local, small-batch beekeepers like Marchese and Rice do not heat or strain their honey before bottling in order to maintain freshness and flavor, as well as preserve its antibacterial, antimicrobial, and other beneficial properties, many of which are diminished or destroyed by the high-heat pasteurization process.

When in doubt, ask the expert: the beekeeper!

All beekeepers have their own methods of hive management and most are eager to share the story behind the process. “We live in an age where everything is about transparency,” said Marchese, "and if you’re not transparent about your business or whatever your practices are, I think you’re going to lose customers.”

Just like local produce, honey is a seasonal product, typically extracted in New England in late summer or early fall. The nectars and pollens of different flowers produce a range of flavors of honey. When you visit a beekeeper, ask about the source or origin of the honey, when the honey was extracted, the kinds of flowers the bees are visiting, and if the honey has ever been heated or filtered. A professional beekeeper will readily know the answers to these questions.

Fresh is best: eat within one year; store in glass and at room temperature

While archeologists have found unspoiled honey in their excavations of 3,000-year-old Egyptian ruins, honey for the average consumer is still best within a year of its harvest. “What happens over a period of time to honey is that the color starts to get really dark, the sugars start breaking down, it loses flavor, and it becomes crystallized,” said Marchese. “There’s nothing like fresh honey out of the hive within the first year, because the minute it’s extracted and it’s put into bottles, it begins to deteriorate.”

Honey can also deteriorate with exposure to climates with extreme temperatures swings like that of Connecticut and New England. It can cause the honey to separate and crystallize again, creating big, coarse crystals. Rice suggests storing honey at room temperature and to “never refrigerate it.”

Another way to ensure fresh tasting honey is to avoid those nostalgic, squeezable, plastic bear bottles and opt for glass containers. Marchese suggests that honey can take on the taste of a plastic container.

Enjoy the spectrum of honey!

While you should support your local beekeepers and seek out local honey when possible, don’t limit yourself to your immediate foodshed. Marchese suggests experimenting and trying different regional honeys on your travels. “Honey is personal. If it’s a good-quality honey and it’s fresh, it should taste good,” she said. “As a foodie, it’s such an amazing experience, like drinking a different bottle of wine. You don’t want to limit yourself to the same bottle of wine all the time, so take a trip and try honeys in other places.”